Originally published in 2006, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic is a graphic memoir that led Alison Bechdel to commercial and critical success. Reminiscent of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Fun Home explores the relationship between Alison and her closeted father, Bruce Bechdel, to shed light on themes such as gender, the coming-out process, and the complicated dynamics of family life. The exploration of these themes are facilitated through discussions of death, life, and literature–triggered by Alison’s efforts to illustrate an accurate portrait of her complicated connection with her father, particularly after he commits suicide.

Alison and her father share many traits: they are both queer (even though the father remains closeted and married to his wife throughout the entire duration of the memoir), they both have a love for reading and for art, and they both wish that they were born the opposite sex. Despite these similarities, they never seem to forge a strong and intense bond due to their reserved personalities and their divergence in terms of gendered affiliations. Whereas Bruce tends to express traits that can typically be approached as feminine, Alison admits that she has been “a connoisseur of masculinity” (95) since she was a child. Thus, even though their share many similarities, their divergence in terms of their gender alignment creates significant tension between the two characters.

Not only does Alison approach herself and her father as “inversions” of each other, but she also makes note of how she struggles to emphasize her masculinity while her father struggles to prevent her from expressing it. She approaches her father’s attempts to feminize her as an almost pathetic effort embody femininity (vicariously) through his daughter, which leads to what Alison calls “a war of cross purposes” that is “doomed to perpetual escalation” (98). Thus, differences of gender are not invoked to uphold the division between men and women, but rather, to illustrate the differences and tensions that exist between Alison and her father.

Bruce’s reserved and temperamental nature is attributed to the fact that he’s had to keep his sexuality a secret due to his upbringing in a society where homosexuality is considered a disgrace. It is suggested in the memoir that Bruce’s repressed nature, his wife’s request for a divorce, and the fact that Alison is able to live an open life as a lesbian (whereas he was not) are the events that prompt him to commit suicide by running in front of a truck. This suicide is the event that prompts Alison to explore her father’s life through memoir, while in turn coming to a more enlightened understanding of the influence that she and her father had on each other. This exploration, however, does not take place in a linear or organized fashion. Fun Home is as a pastiche or decoupage of many elements presented in a non-chronological fashion. The comic panels are supplemented by snippets of other literary texts, photographs, letters, and even newspaper clippings. Furthermore, the narrative itself is supplemented with Bechdel’s interpretations of the events that she lived, in addition to theoretical interventions from areas such as gender and psychoanalysis.

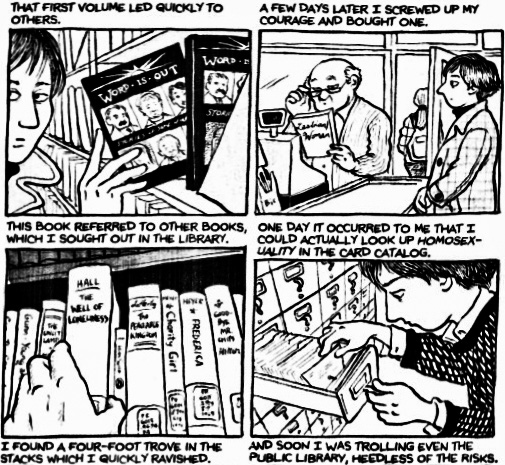

I am deeply interested in the role of literature and literary texts in Fun Home, not only because they add more depth and nuance to the memoir, but also because literature (particularly novels) is a crucial element that must be kept in mind when interpreting and understanding the central developments in the graphic memoir. For instance, literature is the catalyst that helps Alison to discover that she’s a lesbian–leading her to describe her lesbianism as “a revelation not of the flesh, but of the mind” (74). At the age of thirteen, she first encounters the word “lesbian” in a dictionary. She later reads a book focused on offering biographies of queer figures, which leads her on an obsessive mission to read and consume as many queer texts as she possibly can, such as E.M. Forster’s Maurice and Radcliffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness.

The very act of accessing and reading this literature is depicted as a deeply political and almost revolutionary act, for it entails developing the courage to buy these books in spite of their overtly queer titles, or to borrow them from public libraries, “heedless of the risks” (75). These books inspire her to attend a gay union meeting at her university, and to come out to her parents in a letter. Whereas her father seems quite accepting of her sexuality, claiming that “everyone should experiment” (77), her mother responds with mild disapproval, approaching her lesbianism as “a threat” (77) to her work and her family.

Literature is associated with almost every single significant event that takes place in the novel. Alison’s first relationship blossoms when she meets a poet named Joan. Every time they are shown in bed together, they are surrounded by novels and other books. The images depict them reading even when being intimate with one another, and they critique and analyze books even when sprawled naked on their beds (see pages 80-81). The importance of books is her life is unsurprising when taking into account that her father was an English teacher at their local high school, and he spent a lot of time recommending and discussing books with Alison.

Even though Bruce engages in sexual acts with other men, and even boys, the memoir highlights novels and literature as the outlet of escapism that Bruce used to express his sexual frustrations, and even his subconscious sexual desires. His favorite books, such as Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Joyce’s Ulysses, touch upon matters and themes that are central to Bruce’s characterization. The Great Gatsby, for instance, highlights the pains of yearning for someone or something we cannot possess, whereas Ulysses depicts how characters can cross each other’s paths without affecting one another in a significant way (reflecting Alison’s complex relationship with her father). Given how closely Bruce’s books are tied to his suppression, his secrecy, and his hidden desires, it is no wonder that his wife gets rid of most of his book collection after he dies.

It is literature that allows Bruce and Alison to achieve a degree of closeness that they’ve never felt before. It turns out that Alison ends up taking English with her father in twelfth grade, and she realizes that she really likes the books that her father wanted her to read, such as J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. She becomes deeply invested in discussing these books with her father within the classroom–and her interest leads her to develop “a sensation of intimacy” (199) that she has never felt before with her father. When Alison leaves to college, she grows even closer to Bruce, calling him every once in a while to discuss the books that she reads for her English class. Their connection reaches a peak when Bruce lends his daughter a copy of Earthly Paradise by Colette (an autobiography with lesbian themes) even though she has not revealed her lesbianism to him. The book sparks a conversation between the two, leading Bruce to open and honestly discuss his sexual orientation with Alison for the first time.

Literature becomes the agent that allows Alison to forge a connection with her father. Although she admits that her intellectual connection and her intimacy with her father is seen as unusual to other people, she still seems to thoroughly enjoy and appreciate it. Alison does, however, lament that they “were close. But not close enough” (225). However, despite the fact that they were not as close or as intimate as she wanted them to be, she cherishes the fact that “he was there to catch [her] when [she] leapt” (232).

I can’t even begin to describe how much I enjoyed this memoir. It is complex, rich, funny, heartbreaking, and deeply insightful. I’m sure that this book is going to contribute significantly to my academic work, and I can’t wait to re-read this memoir in the near future.

You can purchase a copy of Bechdel’s memoir by clicking here.

Work Cited

Bechdel, Alison. Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007. Print (Paperback edition).

Awesome analysis. Few reviews focus on the gender reversal and the complexity of it all. Also, I’m not sure that anyone spelled out the possibility that Bruce commits suicide because Alison can live an out life (as a lesbian, as a masculine woman, as a younger person) and he (as a gay/bi man, as a feminine man, as an older person) couldn’t. The interweaving strands of masculine-feminine, male-female, younger-older, power-powerlessness etc. go a lot deeper that it looks at the first read. I’m at my 6th or 7th read, and I still discover new things.

Thank you so much for your comments! Fun Home is such a rich and complex graphic novel, and you’re right in pointing out how the work often oscillates between many problematic binaries that we all encounter every day. I’ve read it many times as well, and each time I’m captivated by its intertextuality and depictions of gender and sexuality. I also wonder if Alison’s livability influenced Bruce’s suggested suicide. The text just complicates our ability to fully “know” the truth.

What ever the truth may be, even if it was a suicide or an accident is not clear. But generally I think that seeing a younger generation who can live an open life, after hiding for a lifetime can have a pretty devastating effect, emotionally. On the other hand, Bruce could have moved to NY and lived more openly. His motivations are not quite clear.